How Your Mind Can be Your Greatest Financial Asset or Greatest Liability

FINANCIAL ADVICE | GUIDANCE | INSIGHTS | OBSERVATIONS

Why We Get Right Thinking Wrong

We’ve mentioned before that having the right information at the right time is the basis for good decision-making. In this sense, the power of knowledge is pivotal to success.

Sadly, knowledge isn’t all we need – there’s a whole lot more that matters. Here’s why,

Most of us view human decision-making as a rational process where we use our mental faculties to calculate the best way to achieve our goals. Because we have educated minds and a clear sense of what we want to achieve, we need only take a little time to choose the best course of action, and once we commit to it results will follow.

Right?

Wrong! Investigations from different areas of cognitive science have shown that human decisions and actions are influenced by intuition and emotional responses more than was previously thought.

Couple this with insights from behavioral economics guru, Daniel Kahneman, and suddenly, we discover that when it comes to making clear, logical and beneficial financial decisions, we’re on shaky ground.

“We are prone to believe what we want to believe rather than what the evidence supports.”

– Daniel Kahneman

The 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize winner developed something called “dual process theory,” that recognizes that our brains use two different systems of thinking to make decisions.

System 1 (thinking fast) is our instinctive way of thinking. It’s like being on autopilot, and helps us make snap judgments or react to situations without much effort. System 2 (thinking slow) is our far more deliberate way of thinking. It requires more concentration, and is needed to solve complex problems, weigh options, and make decisions.

Because System 2’s thinking is tiring and demanding, we tend to rely on intuition (System 1 thinking) even when we need to solve complex problems or weigh options. Kahneman’s research is supported by this gem from behavioral economist, Professor Dan Ariely.

“Most people’s financial decision-making falls short of rationality, in the sense that our intentions and our behaviors are often not in agreement. We also routinely have inconsistent beliefs and preferences and we habitually make mistakes in reasoning.”

– Behavioral Economist, Prof Dan Ariely –

Predictably Irrational

Professor Ariely stresses that even the most analytical thinkers are predictably irrational – and the really smart ones acknowledge and address their irrationalities. What about you?

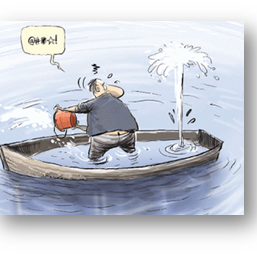

Notice that our first problem lies in the way we think and means we may find ourselves navigating our way through life in a boat full of holes. Our second problem lies in the myriad personal motivations, theories and emotions that cloud our financial decision-making.

Many people hold inconsistent beliefs, illogical theories and personal biases: they often act impulsively, impatiently, and out of a sense of entitlement or thirst for instant gratification.

A bucket-load of holes

Sticking with our maritime metaphor, we find that – on top of a boat full of holes – there’s a long list of problems with our rudders that make our boats hard to steer. These problems are called cognitive biases.

Brace yourself – you’ll recognize many!

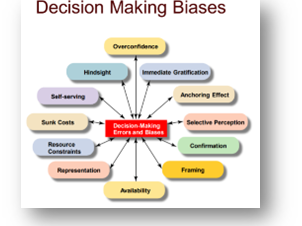

Cognitive Biases

Unconscious biases are shortcuts that our brains take without our noticing, and these biases influence our thoughts and behaviors.

We’re all in the same boat – if we have a brain, we have biases. Who we are friends with, which country we’re from, what social media we use, where we went to school…all these things, and a gazillion others, affect how we see the world and create implicit biases.

These biases arise from the brain’s reliance on mental shortcuts to simplify complex information processing. They can render individuals blind to their own cognitive limitations in shaping perceptions and decisions.

These biases significantly impact decision-making by influencing perception, where individuals selectively process information aligning with existing beliefs.

Attitude-wise, these biases may lead to overconfidence or risk aversion, impacting decisions based on inflated self-assessments or fear of losses. In terms of investment behavior, biases anchor individuals to initial information and encourage persistence in endeavors based on past investments rather than objective evaluations.

Recognizing and addressing these cognitive biases is crucial for fostering more rational and informed decision-making, and raising our awareness to navigate potential pitfalls.

It is very difficult (and often dangerous) to make really important life-changing decisions because we’re all susceptible to a formidable array of decision biases. There are more of them than we realize, and they come to visit us more often than we like to admit.

Our Most Common Biases

Several cognitive biases have gained recognition due to their pervasive influence on human decision-making, affecting everything from personal decision-making to business decisions. There are loads of biases to be aware of, and importantly, these invariably have an emotional component that comes into play. Here’s a heavyweight example:

The Bathroom Scale Test

It’s probably fair to say that most of us don’t like weighing ourselves but still do every now and then. We don’t relish getting naked, looking in the mirror (wince!) and hopping on the scale. But notice how our behavior varies with the number displayed.

When it’s more or less matching our expectations, we move on with our day.

Yet, when it’s not, we freak out and start doing absurd things – removing and putting the battery back, giving the scale a hefty shake – even moving the scale to a different part of the bathroom.

Here are some of the most notable biases, with examples (here and there) to encourage you to notice these biases in yourself, and see how your behavior and emotions follow them.

Confirmation Bias: The tendency to favor information that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs or values. “Thought so, let’s do it!”

Availability Bias: Overestimating the importance of information readily available, leading to skewed perceptions and judgments.

Anchoring Bias: The reliance on the first piece of information encountered (the anchor) when making decisions, even if it is irrelevant.

Time-stressed people have a tendency to skim information and gather the parts they agree with and act upon these.

Overconfidence Bias: The tendency to overestimate your own abilities, knowledge, or the accuracy of your beliefs.

Hindsight Bias: The disposition to perceive events as having been predictable after they’ve already occurred. You’ve seen it or done it – gone to support your team, chewed your fingernails to the elbows, until they win it with the last kick of the game.

“I never doubted they’d win!” you announce proudly.

![]() Really?

Really?

Because we fool ourselves into thinking we knew more about an event before it happens, hindsight bias restricts our ability to learn from the past. It makes us overconfident about future predictions and makes it hard to separate fact from B.S.

Being wrong about stocks can be devastating. It can be a real blow to one’s confidence and bank account. It’s no wonder that people in this profession have a lot of stress.

Loss Aversion: The inclination to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains, leading to risk aversion.

Endowment Effect: The tendency to give higher value to things merely because a person owns them. “Bob’s heavily invested in Enron, and look at him – he’s loaded!!!”

Regret avoidance: “If the stock goes up, I’ll miss out on my payday and will be kicking myself for the rest of my life.” Regret avoidance plays a huge role in decision making, even amongst experienced traders.

A.K.A. Price anchoring: “The stock was worth double a year ago. I’m down 50% and want to gain my money back before I sell.”

Sunk Cost Fallacy: The inclination to continue an endeavor due to the resources already invested, despite a lack of future viability. “I’ve staked the farm on it, and will lose everything if I bail out now.”

Status quo bias: it’s easier to do nothing rather than making a change. This leads to overconcentrated portfolios with outsized risk.

Familiarity Bias: employees feel that because they work for the company, know the management team, and understand the business, their stock will fly. They also believe they’ll be the first to know if things are getting worse. Unfortunately, familiarity and confidence don’t lead to better stock market returns. In fact, they can mask another dangerous reality, as ENRON employees discovered. ‘Enronomics’ is the term given to how executives hid the truth from shareholders back in 2001.

Everyone is susceptible to cognitive biases, and we’re sure you can relate to one or two (maybe all) of those listed above.

We know a lot about how flawed human reasoning is, but surprisingly little about how to repair it. Here are some guidelines you can use to help reduce negative impacts of cognitive biases, to level up your thinking, to refine your beliefs and form more accurate views.

Be aware of common biases. Knowing about the most common mental shortcomings our minds tend to have is a useful first step to make you more careful when forming judgments or making decisions.

Reflect on past mistakes. Looking for patterns in how you’ve perceived prior situations and where you might have made mistakes can significantly reduce the chances you repeat a similar mistake. They may help you rebound and carry on as a better person.

Seek multiple perspectives. Asking others for their input can help us find potential blind spots which we wouldn’t otherwise.

Embrace the opposite. Trying to understand an issue from multiple sides can help you understand the bigger picture and make more accurate decisions.

Consider that you might have been wrong (and that’s okay). Being open to the idea of having been wrong can be painful in the short term, but in the long term it will make you a better critical thinker and a better decision maker.

“Discovering you were wrong is an update, not a failure, and your worldview is a living document meant to be revised.”

Julia Galef – American co-founder of the Center for Applied Rationality and author of The Scout Mindset.

We all have cognitive biases, but hopefully the above practical guidelines and resources can help you to recognize them and reduce their negative impact on your decision-making.

At WestStar we believe that the case for seeking financial guidance is watertight. Working with an experienced financial advisor is beneficial because it brings knowledge and true objectivity to your decision-making. An experienced financial advisor will help you get to grips with your cognitive biases and emotional responses, so you can set yourself up for a strong financial future.

If you have questions about your specific circumstances, or want to talk about developing a financial plan to address your goals and aspirations effectively, please get in touch.

We welcome the opportunity to chat with you and wish you every success in the future.

Sam Gullette & Erik Alexander

Sam Gullette, CFP®, CLU®

Certified Financial Planner™

‘My mission in life is to help people take control of their money and avoid financial stresses. My clients are successful professionals and executives, many of whom are compensated heavily with company stock. Together we maximize their wealth-building opportunities, minimize taxes, and make sure their family is protected if life throws them a curveball.’

Erik Alexander

Financial Consultant

‘I work with professionals and executives who are compensated through various forms of company stock. They have more money than time and struggle to balance the key aspects of their lives. Their decisions affect others, and they feel a huge responsibility towards making them wisely. I enjoy helping them solve their complex problems, and being counted on for their and their families’ financial wellbeing.’